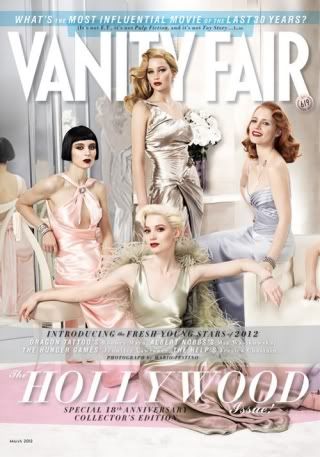

End to end: Rooney Mara ("The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo"), Mia Wasikowska ("The Kids Are All Right"), Jennifer Lawrence ("Winter's Bone"), Jessica Chastain ("The Help"), Elizabeth Olsen ("Martha Marcy May Marlene"), Adepero Oduye ("Pariah"), Shailene Woodley ("The Descendants"), Paula Patton ("Deja Vu"), Felicity Jones ("Like Crazy"), Lily Collins ("Mirror, Mirror") e Brit Marling ("Another Earth").

Showing posts with label Jessica Chastain. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jessica Chastain. Show all posts

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Vanity Fair and the top most promising actresses of Hollywood

End to end: Rooney Mara ("The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo"), Mia Wasikowska ("The Kids Are All Right"), Jennifer Lawrence ("Winter's Bone"), Jessica Chastain ("The Help"), Elizabeth Olsen ("Martha Marcy May Marlene"), Adepero Oduye ("Pariah"), Shailene Woodley ("The Descendants"), Paula Patton ("Deja Vu"), Felicity Jones ("Like Crazy"), Lily Collins ("Mirror, Mirror") e Brit Marling ("Another Earth").

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Tree of Life (2011) [in english]

Jack (Sean Penn) is a lost soul. Surrounded and sunk in the walls of his own existence, distorted fortresses of glittering glass and slanted cement, he recalls his past.

Does it by receiving the genuine humanity Malick depicts in his early films. Does it by reaching the archetype of Men: a disturbing but gracious littleness, an anguished and fearful search for the reason of everything, strong in itself but fragile against nature. What remains is not the feeling of a textual querying, but of a painted and played one. This is Terrence’s freest film, his most improvised and sincere walk, with flavor of sunlight, the only light he and DP Emmanuel Lubetzki («The New World», «Children of Men») admitted to plant this Tree. Protests against the film’s fragmentation seem unfair to me for what sustains the screenplay and the wide-length camera is the ensemble of great moments, just like Stanley Kubrick once stated a film should be made of.

When we’re back in 1950 to the O’Brien’s, Jack searches only for the reconciliation with his father (Brad Pitt), a tough and conservative but passionate man whose manners molded the kid’s growth and affirmation in the years that kept coming. But nothing is more than a profound haste from Jack’s solitude, a cover to an intimate and corrosive wish to find a meaning for his whole life. And so he dives and peeks back in those distant times for a glint of innocence, a grimace of commotion, a footstep of bewilderment he may once have taken. Anything to shake or solve the detachment, the displeasure, the disenchantment he feels today.

When we’re back in 1950 to the O’Brien’s, Jack searches only for the reconciliation with his father (Brad Pitt), a tough and conservative but passionate man whose manners molded the kid’s growth and affirmation in the years that kept coming. But nothing is more than a profound haste from Jack’s solitude, a cover to an intimate and corrosive wish to find a meaning for his whole life. And so he dives and peeks back in those distant times for a glint of innocence, a grimace of commotion, a footstep of bewilderment he may once have taken. Anything to shake or solve the detachment, the displeasure, the disenchantment he feels today.

And that’s when we fall. We fall and we keep falling, through a spiral of colored mosaics, of swinging carved rocks, of voluptuous bubbly and refreshing sea waves, of foaming flooding cataracts, of sunflower fields, of worshiped trees. Back at the surface, panting, we will already be part of the story of Jack’s family. Mom (Jessica Chastain) and dad still lay down on the grass under the touching passion of their youth, bathed by twinkling light honoring the mystery of the touch, the hug, the breeding. Believing or not that the storyboard was overthrown by some at-the-moment appreciation, we will never miss details such as the mother carrying his little baby away from a man in a seizure.

Before we witness the unrolling of one of the most beautiful “father-son” relationships the cinema has ever met, we’re caught in a scale of “whys” and travel to the dawn of time to question the purpose of all existence. Malick studied the cosmos with material from NASA and with a metaphoric editing that builds the whole film he created time and spaceless sequences and essayed on biology and astronomy: beams and explosions of colors and shapes, stars and meteorites, gases and lava, liquid and rock, fog and fish, landscape and dinosaur, microscopic life and magnanimous planetary aurora, inspired in «2001: Space Odyssey», while listening to the excruciating and glorious «Lacrimosa», from «Requiem for a Friend», from Zbigniew Preisner.

Before we witness the unrolling of one of the most beautiful “father-son” relationships the cinema has ever met, we’re caught in a scale of “whys” and travel to the dawn of time to question the purpose of all existence. Malick studied the cosmos with material from NASA and with a metaphoric editing that builds the whole film he created time and spaceless sequences and essayed on biology and astronomy: beams and explosions of colors and shapes, stars and meteorites, gases and lava, liquid and rock, fog and fish, landscape and dinosaur, microscopic life and magnanimous planetary aurora, inspired in «2001: Space Odyssey», while listening to the excruciating and glorious «Lacrimosa», from «Requiem for a Friend», from Zbigniew Preisner.

The second half of «Tree of Life» stabilizes but won’t run away from its prior path. The style remains unconventional in the use of colors, in the composition and framing, in the actors and camera almost improvising, intensifying the naturalistic ethereal tone that has been gathering a legion of fans since «Badlands» (1973). It all flows like a river, alive and breeding, the same way the director asked Alexandre Desplat to create the musical score. Jack’s mother resembles some smile, tenderness, protection, consolation, the joyful task of being a child forever, while the father stands for toughness, respect, discipline and the difficult task of growing older.

The second half of «Tree of Life» stabilizes but won’t run away from its prior path. The style remains unconventional in the use of colors, in the composition and framing, in the actors and camera almost improvising, intensifying the naturalistic ethereal tone that has been gathering a legion of fans since «Badlands» (1973). It all flows like a river, alive and breeding, the same way the director asked Alexandre Desplat to create the musical score. Jack’s mother resembles some smile, tenderness, protection, consolation, the joyful task of being a child forever, while the father stands for toughness, respect, discipline and the difficult task of growing older.

But Malick never denies the compassion he feels for both. Maybe this is where the film flattens a little but it is still beautiful to watch the inevitable roads Jack and his brothers walk towards a more ungrateful and harsher view of the world.

In the end, the defiance of a child who feared his father and swore he wanted him dead gets sharpened in his middle-aged face. And this is where the director’s ecstasy, almost surrealistic, causes confusion and provides some thoughts for the negative reviews. In this climax boils the greatest challenge of interpretation of this picture. As far as I’m concerned, Jack surrenders to faith. And by saying this I may be opening another breach for the skeptics who found a literary pretenciousness in the voice-off. As for me, it complements the image just fine. Because it comes not from a preached religiousness but from a prayed right-of-his-chest yarn. Jack surrenders to the simplicity of the grass, of a beam, of a conversation, of a relationship, of a hand-on-hand walk, of the little things the nature offers (like the little wounded bird, in «The Thin Red Line»). Of the hug, you see. The hug little Jack can’t avoid to give to the man who treated him with such familiarity and conflict, something which will take us to the final forgiveness, for father and son have become alike. And there’s the beach, freedom, just like in Truffaut’s «400 Blows». The answers stay floating around but Malick posits his version of truth (whether or not we believe in such): the joy in everything, from the baby’s first steps to the wrinkled old hand; the grace of existence within the unattainable relationship between the cosmic and the momentary, between the big-picture and the deepest intimacy. In the little things and in the beauty of its imperfection.

In the end, the defiance of a child who feared his father and swore he wanted him dead gets sharpened in his middle-aged face. And this is where the director’s ecstasy, almost surrealistic, causes confusion and provides some thoughts for the negative reviews. In this climax boils the greatest challenge of interpretation of this picture. As far as I’m concerned, Jack surrenders to faith. And by saying this I may be opening another breach for the skeptics who found a literary pretenciousness in the voice-off. As for me, it complements the image just fine. Because it comes not from a preached religiousness but from a prayed right-of-his-chest yarn. Jack surrenders to the simplicity of the grass, of a beam, of a conversation, of a relationship, of a hand-on-hand walk, of the little things the nature offers (like the little wounded bird, in «The Thin Red Line»). Of the hug, you see. The hug little Jack can’t avoid to give to the man who treated him with such familiarity and conflict, something which will take us to the final forgiveness, for father and son have become alike. And there’s the beach, freedom, just like in Truffaut’s «400 Blows». The answers stay floating around but Malick posits his version of truth (whether or not we believe in such): the joy in everything, from the baby’s first steps to the wrinkled old hand; the grace of existence within the unattainable relationship between the cosmic and the momentary, between the big-picture and the deepest intimacy. In the little things and in the beauty of its imperfection.

Does it by receiving the genuine humanity Malick depicts in his early films. Does it by reaching the archetype of Men: a disturbing but gracious littleness, an anguished and fearful search for the reason of everything, strong in itself but fragile against nature. What remains is not the feeling of a textual querying, but of a painted and played one. This is Terrence’s freest film, his most improvised and sincere walk, with flavor of sunlight, the only light he and DP Emmanuel Lubetzki («The New World», «Children of Men») admitted to plant this Tree. Protests against the film’s fragmentation seem unfair to me for what sustains the screenplay and the wide-length camera is the ensemble of great moments, just like Stanley Kubrick once stated a film should be made of.

And that’s when we fall. We fall and we keep falling, through a spiral of colored mosaics, of swinging carved rocks, of voluptuous bubbly and refreshing sea waves, of foaming flooding cataracts, of sunflower fields, of worshiped trees. Back at the surface, panting, we will already be part of the story of Jack’s family. Mom (Jessica Chastain) and dad still lay down on the grass under the touching passion of their youth, bathed by twinkling light honoring the mystery of the touch, the hug, the breeding. Believing or not that the storyboard was overthrown by some at-the-moment appreciation, we will never miss details such as the mother carrying his little baby away from a man in a seizure.

But Malick never denies the compassion he feels for both. Maybe this is where the film flattens a little but it is still beautiful to watch the inevitable roads Jack and his brothers walk towards a more ungrateful and harsher view of the world.

A Árvore da Vida (2011) [português]

Jack (Sean Penn) é uma alma perdida. Rodeado e imerso pelas muralhas da sua própria existência, fortalezas distorcidas, de vidro brilhante e betão oblíquo, recorda agora o seu passado: sua infância, seus irmãos e suas brincadeiras, seus pais e seus ensinamentos. Fá-lo recebendo em si a genuína humanidade que Malick trabalha nos seus anteriores filmes. Fá-lo procurando ser o arquétipo do Homem, na sua ora perturbadora ora graciosa pequenez, na sua angústia e temor na busca pela razão de tudo, na sua força consigo mesmo e na sua fragilidade contra a natureza, no seu desconfiado mas emocionado receber das mais ténues e das mais meteóricas coisas, na sua determinada e sortuda, mas hesitante e desgraçada vontade de ser e estar em todos os dias de uma vida. A ideia que fica não é a de que Terrence coloca questões, mas sim de que as pinta e toca. Este é o seu filme mais livre, de caminhada mais improvisada e sincera, ao sabor da luz natural do sol, a única que, com o director de fotografia Emmanuel Lubetzki («O Novo Mundo», «Os Filhos do Homem»), admitiu para plantar esta Árvore. Um protesto contra a fragmentação do filme parece-me injusto, pois o que alicerça o trabalho deste argumento e desta câmara em grande-angular é o conjunto de grandes momentos, como Stanley Kubrick em tempos defendeu que devia ser feito um filme.

Quando voltamos até 1950, para junto da família O’Brien, Jack apenas procura a reconciliação com o seu pai (Brad Pitt), homem duro e conservador, mas íntegro e apaixonado, cujo tratamento moldou o seu crescimento e afirmação na idade que lhe foi sendo acrescentada. Mas tudo não passa de um ainda mais profundo ímpeto de solidão espiritual, de uma capa para um desejo íntimo e corrosivo de encontrar propósito para toda a sua vida. Assim, mergulha e busca, naqueles longínquos tempos, um raio de inocência, um esgar de comoção, uma pegada de deslumbramento que outrora tenha dado, que abale ou reconforte o desapego, o desgosto, o desencanto que hoje sente. É aqui que caímos. Caímos e vamos caindo, numa espiral sem paredes e sem fundo, feita de mosaicos coloridos, de dançantes recortes rochosos, de voluptuosas, borbulhantes e refrescantes ondas do mar, de cataratas espumantes e diluviais, de campos de girassóis, de árvores deificadas. Quando vimos à tona e respiramos ofegantes, já entrámos na história da família de Jack. Pai e mãe (Jessica Chastain) ainda se deitam na relva, sob a comovente paixão dos primeiros tempos, banhados por intermitências de luz que homenageiam o mistério do toque, do abraço, da concepção. Creia-se ou não que a planificação foi substituída pelo mero captar, nunca deixaremos escapar deliciosos detalhes como a mãe que pega o filho ao colo e o afasta da sofredora imagem de um homem em ataque epiléptico.

Quando voltamos até 1950, para junto da família O’Brien, Jack apenas procura a reconciliação com o seu pai (Brad Pitt), homem duro e conservador, mas íntegro e apaixonado, cujo tratamento moldou o seu crescimento e afirmação na idade que lhe foi sendo acrescentada. Mas tudo não passa de um ainda mais profundo ímpeto de solidão espiritual, de uma capa para um desejo íntimo e corrosivo de encontrar propósito para toda a sua vida. Assim, mergulha e busca, naqueles longínquos tempos, um raio de inocência, um esgar de comoção, uma pegada de deslumbramento que outrora tenha dado, que abale ou reconforte o desapego, o desgosto, o desencanto que hoje sente. É aqui que caímos. Caímos e vamos caindo, numa espiral sem paredes e sem fundo, feita de mosaicos coloridos, de dançantes recortes rochosos, de voluptuosas, borbulhantes e refrescantes ondas do mar, de cataratas espumantes e diluviais, de campos de girassóis, de árvores deificadas. Quando vimos à tona e respiramos ofegantes, já entrámos na história da família de Jack. Pai e mãe (Jessica Chastain) ainda se deitam na relva, sob a comovente paixão dos primeiros tempos, banhados por intermitências de luz que homenageiam o mistério do toque, do abraço, da concepção. Creia-se ou não que a planificação foi substituída pelo mero captar, nunca deixaremos escapar deliciosos detalhes como a mãe que pega o filho ao colo e o afasta da sofredora imagem de um homem em ataque epiléptico.

Antes de assistirmos ao desenrolar de uma das mais belas relações “pai-filho” que o cinema já conheceu, estamos presos numa escala de “porquês” e vamos até ao início dos tempos para questionar o propósito de toda a existência. Estudou o cosmos por material da NASA e, sob uma filosofia de montagem simbólica e metafórica que cobre toda a película, criou sequências acima da esfera espácio-temporal e ensaiou sobre o biológico e o astronómico: feixes e explosões de cores e formas, estrelas e meteoritos, gases e lava, líquido e rocha, nébula e peixe, paisagem e dinossauro, microscópico protozoário e magnânima aurora planetária de inspiração em «2001 » , ao som da excruciante e gloriosa «Lacrimosa» de «Requiem for a Friend», de Zbigniew Preisner.

Antes de assistirmos ao desenrolar de uma das mais belas relações “pai-filho” que o cinema já conheceu, estamos presos numa escala de “porquês” e vamos até ao início dos tempos para questionar o propósito de toda a existência. Estudou o cosmos por material da NASA e, sob uma filosofia de montagem simbólica e metafórica que cobre toda a película, criou sequências acima da esfera espácio-temporal e ensaiou sobre o biológico e o astronómico: feixes e explosões de cores e formas, estrelas e meteoritos, gases e lava, líquido e rocha, nébula e peixe, paisagem e dinossauro, microscópico protozoário e magnânima aurora planetária de inspiração em «2001 » , ao som da excruciante e gloriosa «Lacrimosa» de «Requiem for a Friend», de Zbigniew Preisner.

A segunda metade de «Árvore da Vida» estabiliza narrativamente, mas nunca foge ao que já foi. O estilo continua a fugir à convenção, nas cores, na composição e nos enquadramentos, a favor de movimentos improvisados de câmara e actores, intensificando o impacto do tom e atmosfera naturalísticos e etéreos que vêm gerando uma legião de fãs malickianos desde «Noivos Sangrentos», em 1973. Tudo flui como um rio, vivo e com vida para dar, precisamente aquilo que o realizador pediu a Alexandre Desplat, no construir da banda-musical. A mãe de Jack representa a sua lembrança do sorriso, do carinho, da protecção, do consolo, da adorável tarefa de ser criança para sempre, enquanto que o pai é o mordomo da tenacidade, do respeito, da disciplina, e da árdua tarefa de ter de entrar no mundo adulto.

A segunda metade de «Árvore da Vida» estabiliza narrativamente, mas nunca foge ao que já foi. O estilo continua a fugir à convenção, nas cores, na composição e nos enquadramentos, a favor de movimentos improvisados de câmara e actores, intensificando o impacto do tom e atmosfera naturalísticos e etéreos que vêm gerando uma legião de fãs malickianos desde «Noivos Sangrentos», em 1973. Tudo flui como um rio, vivo e com vida para dar, precisamente aquilo que o realizador pediu a Alexandre Desplat, no construir da banda-musical. A mãe de Jack representa a sua lembrança do sorriso, do carinho, da protecção, do consolo, da adorável tarefa de ser criança para sempre, enquanto que o pai é o mordomo da tenacidade, do respeito, da disciplina, e da árdua tarefa de ter de entrar no mundo adulto.

Mas Malick nunca nega a profunda compaixão de ambos. Correndo, correndo, e admitiria que aqui se alonga um pouco, seguimos os troços de educação que Jack e os seus dois irmãos percorreram, no ingrato despontar de uma visão necessariamente cada vez mais frontal do mundo.

No final, a rebeldia de uma criança que temia o pai e que jurava que este o queria morto brutaliza-se na face do presente, e é apenas aqui que o êxtase do realizador, quase surrealista, causa alguma confusão ao público e dá algum material às reacções negativas. É principalmente neste ponto que ferve a dificuldade de interpretação, em pleno clímax. A mim, parece-me que Jack sucumbe à fé. E dizer isto é abrir novo espaço para as vozes mais cépticas, que encontram na constante voz-off um dispositivo demasiado explicativo, e literário, de pretensiosismo poético. Mas não será mero complemento à imagem? Porque se sente efectivamente uma religiosidade que não é pregada mas sim orada como um suspiro e desabafo pessoais de Terrence Malick. Jack sucumbe, acima de tudo, à fé no prazer da simplicidade de uma erva, de um raio de luz, das pequenas coisas que a natureza comporta (como o pequeno pássaro ferido, agoniante imagem de «A Barreira Invisível»), do falar, do relacionar, do dar a mão. Do abraço, aliás. O abraço, aquele que o pequeno Jack não aguenta em não dar ao homem com quem travava tanta familiaridade e tanto conflito, que se traduzirá no perdão final para o pai que o tornou igual a si, numa praia de libertação como nos «400 Golpes», de Truffaut. As respostas continuam no ar mas Malick propõe a sua versão de verdade (quer acreditemos numa ou não): a alegria de tudo, dos primeiros passos à mão idosa e enrugada; a graça da existência na inatingível relação entre o cósmico e o momentâneo, entre o grande-quadro e a pequena intimidade. Enfim, nas pequenas coisas e na beleza da sua imperfeição.

No final, a rebeldia de uma criança que temia o pai e que jurava que este o queria morto brutaliza-se na face do presente, e é apenas aqui que o êxtase do realizador, quase surrealista, causa alguma confusão ao público e dá algum material às reacções negativas. É principalmente neste ponto que ferve a dificuldade de interpretação, em pleno clímax. A mim, parece-me que Jack sucumbe à fé. E dizer isto é abrir novo espaço para as vozes mais cépticas, que encontram na constante voz-off um dispositivo demasiado explicativo, e literário, de pretensiosismo poético. Mas não será mero complemento à imagem? Porque se sente efectivamente uma religiosidade que não é pregada mas sim orada como um suspiro e desabafo pessoais de Terrence Malick. Jack sucumbe, acima de tudo, à fé no prazer da simplicidade de uma erva, de um raio de luz, das pequenas coisas que a natureza comporta (como o pequeno pássaro ferido, agoniante imagem de «A Barreira Invisível»), do falar, do relacionar, do dar a mão. Do abraço, aliás. O abraço, aquele que o pequeno Jack não aguenta em não dar ao homem com quem travava tanta familiaridade e tanto conflito, que se traduzirá no perdão final para o pai que o tornou igual a si, numa praia de libertação como nos «400 Golpes», de Truffaut. As respostas continuam no ar mas Malick propõe a sua versão de verdade (quer acreditemos numa ou não): a alegria de tudo, dos primeiros passos à mão idosa e enrugada; a graça da existência na inatingível relação entre o cósmico e o momentâneo, entre o grande-quadro e a pequena intimidade. Enfim, nas pequenas coisas e na beleza da sua imperfeição.

Mas Malick nunca nega a profunda compaixão de ambos. Correndo, correndo, e admitiria que aqui se alonga um pouco, seguimos os troços de educação que Jack e os seus dois irmãos percorreram, no ingrato despontar de uma visão necessariamente cada vez mais frontal do mundo.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)